Think about all the things you don’t like in real life. Sharks. Spiders. Earthquakes. Bullies. Public speaking. Chances are, if you expose your characters to what you fear, your fiction will flourish because of it. Writers can’t afford to be nice. We’ve got to throw rocks at our characters, as Nabokov famously said. Get them into terrible trouble and hold them there, feet to the fire, until the very end of the story.

Think about all the things you don’t like in real life. Sharks. Spiders. Earthquakes. Bullies. Public speaking. Chances are, if you expose your characters to what you fear, your fiction will flourish because of it. Writers can’t afford to be nice. We’ve got to throw rocks at our characters, as Nabokov famously said. Get them into terrible trouble and hold them there, feet to the fire, until the very end of the story.

Why? Because witnessing other people’s pain and observing how they deal with it keeps readers turning pages. Hopefully, it teaches us something too.

I don’t mean that we should create unrelenting misery; our characters need to experience both ups and downs. I’m no masochist, but since it’s January, I thought the topic of pain was appropriate. For many, this is a month of deprivation and dieting after the holiday excesses. Or a time to force ourselves (again) to start working out at the gym. Just attempting to carry out our new year’s resolutions—and the guilt we feel if we don’t—can cause angst.

Given that this past year has been a challenging one for my family, it helps me to remember that hardship can actually benefit us in the long run. Light can’t exist without darkness. We must experience sorrow to truly feel joy. So in fiction, a dearth of pain can be a problem. When tension fades, so does reader interest. One of my students has a tendency to protect her protagonists, just as she’d do for the people she loves in real life. Her instinct is to keep them happy and safe from harm. Boring. “Stop mothering your main characters,” I tell her, but she still finds it hard to hurt them. She’s not the only writer who struggles with this.

It may be helpful to think of it in exercise terms. Physical pain, the kind we feel when we push ourselves playing sports or working out, is a necessary part of getting stronger. Athletes can’t get to the next level without it. Tearing microscopic muscle fibers helps the fibers rebuild more densely into bigger muscles—scientific evidence that discomfort can be beneficial (as long as we don’t overdo it). I’ve always found it ironic, of course, that in order to flood my system with those bliss-producing endorphins, I have to embrace pain first. But every time, the aches and agony lead me to the ecstasy.

Emotional pain can strengthen us in the same way. Writer Jeanne Weierheiser calls “embracing pain the gateway to growth.” How can you not gift your characters this kind of opportunity? I’m exploring what it means to be a hero in the book I’m writing. To do this, I’m forcing my characters to make mistakes and endure some really bad things. That’s because their journey to transformation is not based on success. Winning isn’t always the best teacher. Setbacks are what make us stronger. Think about your own experiences. Isn’t positive change more likely to occur after periods of heartache and despair? In the end, my protagonist comes to see that she’s learned more from her missteps than her triumphs. It’s through struggle that she discovers who she is.

Emotional pain can strengthen us in the same way. Writer Jeanne Weierheiser calls “embracing pain the gateway to growth.” How can you not gift your characters this kind of opportunity? I’m exploring what it means to be a hero in the book I’m writing. To do this, I’m forcing my characters to make mistakes and endure some really bad things. That’s because their journey to transformation is not based on success. Winning isn’t always the best teacher. Setbacks are what make us stronger. Think about your own experiences. Isn’t positive change more likely to occur after periods of heartache and despair? In the end, my protagonist comes to see that she’s learned more from her missteps than her triumphs. It’s through struggle that she discovers who she is.

The hazards writers create don’t have to be huge and life-threatening. But there should be plenty of small stuff for characters to sweat. Even minor pain can cause emotional upheaval and growth. Things like—

- Change. This is something people tend to be wary of. As Sol Stein writes in Stein on Writing, “Changes in life are fraught with peril. If the perils of major change happen within the covers of a book, the reader will be absorbed.”

- Surprises. There are good and bad surprises. Bad ones in life bring “hurt, sadness, misfortune,” says Stein. “But in books readers thrill to the unexpected. A new obstacle, an unexpected confrontation by an enemy, or a sudden twist of circumstance all start adrenaline pumping and pages turning.”

- Embarrassment. Even in humorous fiction, characters should experience some suffering. Embarrassing situations are a perfect vehicle for this, and they will almost always create interesting plot developments.

Failure is also a reliable source of pain. Most of us have experienced some incidents of failure in real life. When I think of all my unfinished stories and abandoned novels, for instance, I tend to start feeling bad… And yet, my advisors at VCFA taught me that nothing is wasted, every word we write (good or bad) prepares us for what comes next. So, I try to remember that perfection is the enemy of progress, and that Jane Fonda was right when she brought the phrase, “No pain, no gain,” into prominence to promote her exercise videos.

A protagonist in pain can help us answer the following key story questions: Does this person have a goal? What is the purpose of this scene? If your character isn’t suffering, trying to keep from suffering, or trying to make someone else suffer, scenes can start to drag. In fiction, too much happiness can become humdrum.

So, embrace the pain when it comes knocking at your door. Learn from your fiascos and flops. And do something nice for your characters—inflict some misery on them. One day, they’ll thank you for it.

Traditionally published books are only one of many creative platforms available to writers today. To get you started thinking less conventionally, I’ve profiled three alternative options for getting published: podcast fiction, books for hire, and an app featuring text message thrillers. Two provide compensation; one does not. However, they all can teach us valuable lessons about honing our craft, gaining visibility, and discovering new storytelling venues.

Traditionally published books are only one of many creative platforms available to writers today. To get you started thinking less conventionally, I’ve profiled three alternative options for getting published: podcast fiction, books for hire, and an app featuring text message thrillers. Two provide compensation; one does not. However, they all can teach us valuable lessons about honing our craft, gaining visibility, and discovering new storytelling venues.

Helen: How did you get involved in writing books for hire?

Helen: How did you get involved in writing books for hire? Linden: I’d like to do longer pieces [so I can] really dig into research. And there are no royalties with this kind of writing.

Linden: I’d like to do longer pieces [so I can] really dig into research. And there are no royalties with this kind of writing.

Like suspense. Stories need to hook readers from the start. To do that with nothing but tweet-length dialogue isn’t easy, so authors must come up with intriguing ideas to get readers “tapping” to turn pages. And they do, because in every story I read, I was curious to find out what would happen. Founders Prerna Gupta and Parag Chord even echo advice my

Like suspense. Stories need to hook readers from the start. To do that with nothing but tweet-length dialogue isn’t easy, so authors must come up with intriguing ideas to get readers “tapping” to turn pages. And they do, because in every story I read, I was curious to find out what would happen. Founders Prerna Gupta and Parag Chord even echo advice my

It was research librarians who helped Meg Wiviott, author of the picture book, Benno and the Night of Broken Glass, and the YA novel, Paper Hearts, with one of her greatest challenges—finding a German map from 1938 that could provide her with the name of a street in Berlin in the vicinity of the Neue Synagogue. This was “not something that could be googled,” Meg explains, “because Berlin was heavily bombed and damaged at the end of [WWII] and modern day streets might not have existed back in [the year the story was set].”

It was research librarians who helped Meg Wiviott, author of the picture book, Benno and the Night of Broken Glass, and the YA novel, Paper Hearts, with one of her greatest challenges—finding a German map from 1938 that could provide her with the name of a street in Berlin in the vicinity of the Neue Synagogue. This was “not something that could be googled,” Meg explains, “because Berlin was heavily bombed and damaged at the end of [WWII] and modern day streets might not have existed back in [the year the story was set].”

For his fourth book, A Fine and Dangerous Season, Raffel spent time at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston, where he “used a bunch of memoirs, a book of transcripts from the Cuban Missile Crisis, and a book showing what the White House looked like in the Kennedy years.” He also travels to foreign cities to do research first-hand as well.

For his fourth book, A Fine and Dangerous Season, Raffel spent time at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston, where he “used a bunch of memoirs, a book of transcripts from the Cuban Missile Crisis, and a book showing what the White House looked like in the Kennedy years.” He also travels to foreign cities to do research first-hand as well. Her only problem was knowing when to stop. “Research,” Meg says, “is an addictive pit I can easily fall into.”

Her only problem was knowing when to stop. “Research,” Meg says, “is an addictive pit I can easily fall into.”

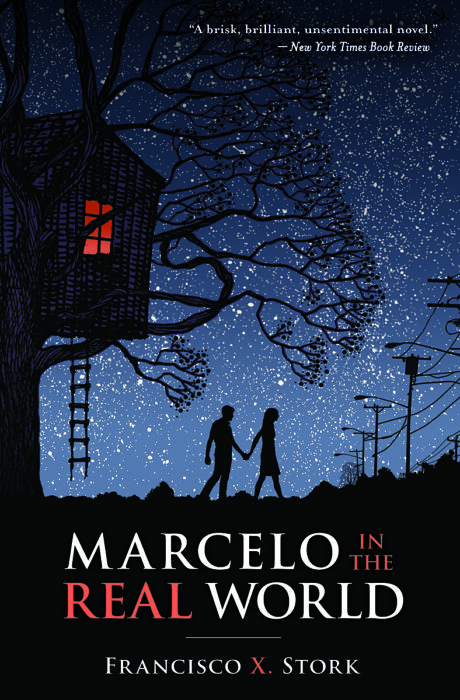

Stork’s message was fortuitously similar. “You must learn to trust your intuition if you want to write characters with heart and soul who live forever in the minds of readers.” Stork defined intuition as “a way of seeing a truth that is not dependent on words.” As the creator of one of my favorite fictional characters, Marcelo Sandoval from Marcelo in the Real World, the author clearly practices what he preaches. The truth of Marcelo, his “soul,” came to Stork in a flash of intuition. Later he tweaked and revised his protagonist, but because he trusted his gut instinct and embraced the “sudden illumination,” an extraordinary character was revealed to him.

Stork’s message was fortuitously similar. “You must learn to trust your intuition if you want to write characters with heart and soul who live forever in the minds of readers.” Stork defined intuition as “a way of seeing a truth that is not dependent on words.” As the creator of one of my favorite fictional characters, Marcelo Sandoval from Marcelo in the Real World, the author clearly practices what he preaches. The truth of Marcelo, his “soul,” came to Stork in a flash of intuition. Later he tweaked and revised his protagonist, but because he trusted his gut instinct and embraced the “sudden illumination,” an extraordinary character was revealed to him. While writers cannot force this kind of insight, Stork claimed that “we can create circumstances that are favorable for its arising.” He cited three writerly disciplines—mindfulness, a sense of play, and honesty—that make it “more likely for the lightning of intuition to strike.”

While writers cannot force this kind of insight, Stork claimed that “we can create circumstances that are favorable for its arising.” He cited three writerly disciplines—mindfulness, a sense of play, and honesty—that make it “more likely for the lightning of intuition to strike.”

The act of linking setting description to character emotion is one way to use the objective correlative, also known as telling it slant. Tell it/slant is all about focusing on details that help the reader understand what you’re trying to convey—like insight into the narrator’s emotional state or a foreshadowing of what’s to come. “The trick is not to find a fresh setting or a unique way to portray a familiar place,” explains writer Donald Maass, “rather, it is to discover in your setting what is unique for your characters, if not for you.” Thus, a fictional environment comes alive partly in its details and partly in the way that characters experience those details.

The act of linking setting description to character emotion is one way to use the objective correlative, also known as telling it slant. Tell it/slant is all about focusing on details that help the reader understand what you’re trying to convey—like insight into the narrator’s emotional state or a foreshadowing of what’s to come. “The trick is not to find a fresh setting or a unique way to portray a familiar place,” explains writer Donald Maass, “rather, it is to discover in your setting what is unique for your characters, if not for you.” Thus, a fictional environment comes alive partly in its details and partly in the way that characters experience those details.

“I love New York City,” she admits. “I love the burning grease smell from the halal carts and the sticky sweet aroma of roasting peanuts that seems to hit me on every corner. My heart swells at the dank wind that a speeding subway train churns up as it pulls out of a station.”

“I love New York City,” she admits. “I love the burning grease smell from the halal carts and the sticky sweet aroma of roasting peanuts that seems to hit me on every corner. My heart swells at the dank wind that a speeding subway train churns up as it pulls out of a station.”

Inspiration is not like mislaid socks or lost buttons. You can’t see, hear or hold it, but you know when it’s gone. Because it’s the New Year, a hopeful time, when people are focused on fresh starts, I thought blogging about the problem might help me get back on track. After all, I’m starting something too—the ending of my novel. But the challenge of tying story elements together and weaving in concepts like crisis, climax and character arc into a brilliant conclusion has temporarily overwhelmed me. I need a creativity reboot!

Inspiration is not like mislaid socks or lost buttons. You can’t see, hear or hold it, but you know when it’s gone. Because it’s the New Year, a hopeful time, when people are focused on fresh starts, I thought blogging about the problem might help me get back on track. After all, I’m starting something too—the ending of my novel. But the challenge of tying story elements together and weaving in concepts like crisis, climax and character arc into a brilliant conclusion has temporarily overwhelmed me. I need a creativity reboot! Walk in nature. Writer Jill Koenigsdorf, author of Phoebe and the Ghost of Chagall, swears by going on long hikes in nature with her dogs. “I find that during my walks, all my senses are more attuned and I tend to slow down and mull ideas over. I will see a raven on a barbed wire fence or a slit-open bag of sand on the side of the road or a piece of torn fabric on a rose bush, and it will trigger a story,” she explains. “I also find if I am stuck writing a certain scene or character in a piece I have already started, that walking outdoors helps me see what the problem is.

Walk in nature. Writer Jill Koenigsdorf, author of Phoebe and the Ghost of Chagall, swears by going on long hikes in nature with her dogs. “I find that during my walks, all my senses are more attuned and I tend to slow down and mull ideas over. I will see a raven on a barbed wire fence or a slit-open bag of sand on the side of the road or a piece of torn fabric on a rose bush, and it will trigger a story,” she explains. “I also find if I am stuck writing a certain scene or character in a piece I have already started, that walking outdoors helps me see what the problem is.

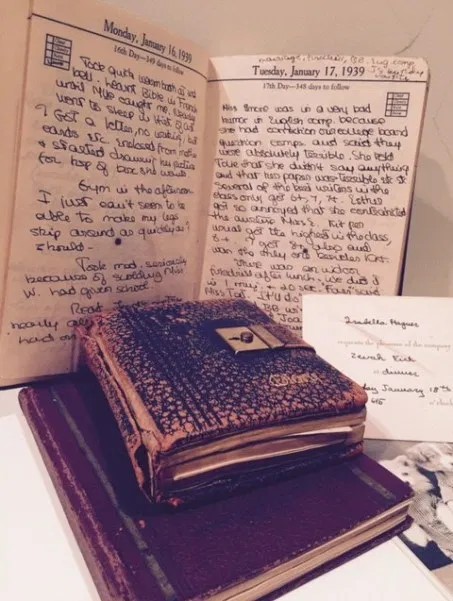

Seek out other people’s stories in whatever forms they take. Consider using unconventional materials. Stories can be found wherever we are, so be open about where to look. Sources like stand-up comedy routines, church sermons, obituaries, maps, yearbooks, brochures, games, restaurant menus, journals and even junk mail can be chock-a-block full of anecdotes and ideas. Recently, my husband and I discovered a stash of his mother’s old diaries. The yellowing pages, antiquated language, and old-fashioned perspective from a different era is a treasure chest of data— charming and sweet and a little bit sad. Reading the words my mother-in-law wrote as a 16-year-old in 1939 has been eye-opening. Bonus materials crammed into her diaries included postcards, dance cards, sketches, and even notes from summer camp friends. My favorite one was addressed to “a girl who can keep her temper well.”

Seek out other people’s stories in whatever forms they take. Consider using unconventional materials. Stories can be found wherever we are, so be open about where to look. Sources like stand-up comedy routines, church sermons, obituaries, maps, yearbooks, brochures, games, restaurant menus, journals and even junk mail can be chock-a-block full of anecdotes and ideas. Recently, my husband and I discovered a stash of his mother’s old diaries. The yellowing pages, antiquated language, and old-fashioned perspective from a different era is a treasure chest of data— charming and sweet and a little bit sad. Reading the words my mother-in-law wrote as a 16-year-old in 1939 has been eye-opening. Bonus materials crammed into her diaries included postcards, dance cards, sketches, and even notes from summer camp friends. My favorite one was addressed to “a girl who can keep her temper well.”

While visiting my eldest son in Oregon this month, I spent a morning picking peas on his farm. After showing me how to choose the plumpest pods that were ready for harvesting, my son handed me a bucket to fill. As I worked my way down the row of trellised vines, peering out from under my sun hat into the dappled green depths, I picked what I thought was every last ripe pod.

While visiting my eldest son in Oregon this month, I spent a morning picking peas on his farm. After showing me how to choose the plumpest pods that were ready for harvesting, my son handed me a bucket to fill. As I worked my way down the row of trellised vines, peering out from under my sun hat into the dappled green depths, I picked what I thought was every last ripe pod.

Pea vision, as I define it, is when something obscure becomes suddenly clear. It’s all about perspective. Writers need to find their form of pea vision too—especially when it comes to characters. Figuring out how a protagonist acts, thinks, feels and talks rarely happens in a single blinding flash of insight. It takes time to get to know a character. When I walked back down that row of peas, I saw things I hadn’t seen before. Why? Because I changed the way I looked at the vines.

Pea vision, as I define it, is when something obscure becomes suddenly clear. It’s all about perspective. Writers need to find their form of pea vision too—especially when it comes to characters. Figuring out how a protagonist acts, thinks, feels and talks rarely happens in a single blinding flash of insight. It takes time to get to know a character. When I walked back down that row of peas, I saw things I hadn’t seen before. Why? Because I changed the way I looked at the vines.

I’m always looking for a competitive edge. Will exercise, coffee, vitamins or a good night’s sleep help me to write better? So, when I read that science has proven meditation actually restructures the brain, I was intrigued. After all, in Silicon Valley where I live, companies like Google, Twitter and Facebook have been offering “Search Inside Yourself” training for years. Classes like Neural Self-Hacking and Managing Your Energy make for lunch hours that “maximize mindfulness” and spark creativity.

I’m always looking for a competitive edge. Will exercise, coffee, vitamins or a good night’s sleep help me to write better? So, when I read that science has proven meditation actually restructures the brain, I was intrigued. After all, in Silicon Valley where I live, companies like Google, Twitter and Facebook have been offering “Search Inside Yourself” training for years. Classes like Neural Self-Hacking and Managing Your Energy make for lunch hours that “maximize mindfulness” and spark creativity. In a post (“

In a post (“