Like the apple that fell on Isaac Newton, a new insight smacked me over the head last week. It happened after I watched a Facebook video, “Real-Life Superheroes are among Us,” by photographer John Rossi. In it, Rossi and his team of professionals took six kids living with serious disabilities and dressed them up as superheroes for an epic photoshoot. “The whole idea,” Rossi explained, “was to take the things that are weaknesses for kids such as cancer and other diseases and turn them into strengths.”

Instantly, I saw the connection. A writer’s ability to turn a weakness into a strength is like discovering a character’s secret power. When a handicap becomes a hidden talent, it’s empowering. Transformation that’s not just about change, but also about acceptance, reassures us. It gives readers hope. If we’re able to see our faults as potential advantages, aren’t we more likely to accept and embrace who we are?

There are two kinds of character weaknesses. The first is a physical or emotional trait that the hero is born with, something that’s hardwired or hereditary. The second is a kind of coping mechanism that’s developed to compensate for a vulnerability or a wound inflicted in the hero’s backstory. Whatever the origin, this deficiency, which has become part of the character’s belief system, is what’s preventing him from achieving what he wants.

Or is it?

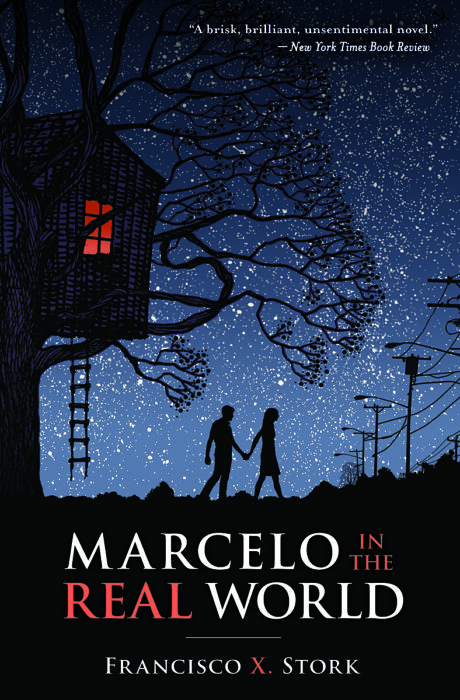

In Francisco X. Stork’s Marcelo in the Real World, the protagonist, Marcelo, struggles with an autism-like condition. He hears music that nobody else can hear, has trouble interpreting people’s words and behavior, and struggles to make sense of a world he sometimes fears and doesn’t understand. And yet it’s his so-called disabilities that enable Marcelo to right a terrible wrong, fight injustice more courageously and effectively than others, and win the love of a smart and beautiful co-worker. Marcelo’s cognitive impairment is what makes it possible for him to succeed.

Marcelo understands this. “The term ‘cognitive disorder’ implies that there is something wrong with the way I think or the way I perceive reality,” he says. “I perceive reality just fine. Sometimes I perceive more of reality than others.”

Learning to think differently about how we see our shortcomings helps us release negative emotions and assumptions. The process of revising one’s belief system can free characters from the power their backstory wound holds over them.

Turning flaws into assets also makes for great plot twists and satisfying endings. In the fable of the lion and the mouse, when the mouse is caught by the lion, his small size and lack of strength makes him easy prey. But the mouse begs for his life, promising to repay the lion, and the king of the jungle, amused, sets him free. Later, when the lion is netted by hunters, the tiny mouse is able to free him by inconspicuously gnawing through the ropes that bind the giant beast. Suddenly, the mouse’s tiny size has become a strength, not a weakness.

It’s important to remember, however, that fictional faults are a double-edged sword. They result in both good and bad consequences. So, writers shouldn’t let their characters disregard or excuse their worst traits. The hero still needs to strive to be better.

In Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic novel, The Secret Garden, protagonist Mary Lennox does try to better herself. But not until the book is well under way. Sickly, bad-tempered, and unsightly, she’s an orphaned child who’s never been loved, raised and kowtowed to by servants. But when she’s sent from India to England to live with a reclusive, hunchbacked uncle, her life undergoes a radical change.

It’s Mary’s shortcomings that cause her to act in unorthodox ways. For example, one night when Mary hears mysterious cries, she gets up, angry and unafraid, and wanders around the manor house. Eventually she discovers Colin, her uncle’s crippled son, and yells at him in a way no one else has ever dared to. Miraculously, her outburst intrigues her cousin and stops his temper tantrum! Here again, it’s the protagonist’s faults—like her impatience, impulsivity, and temper—that enable her to achieve her goals. Goals that include healing herself, reviving the mystical, “secret” garden, and helping Colin to walk again.

Movie characters exemplify this paradox too. Just look at Forrest Gump. Bullied as a child because of his marginal intelligence and physical disability (his curved spine required him to wear leg braces that made it hard to walk), Forrest had the deck stacked against him. But thanks to the bullies who taunted and chased him, he learned how to run fast, becoming a world-class runner and athlete. Thanks to his low I.Q. and naivety, he did things no one else believed possible, simply because he didn’t know he couldn’t. Football star, war hero, and recipient of the Medal of Honor, Gump has been called “the greatest movie character of all time.” I believe he struck a nerve because so many people know what it’s like to feel as if they’re not “good enough.” Fortunately, the stories we write can help convince readers that despite their flaws—and maybe even because of them—they are deserving. They do matter. And they’re good enough just as they are.

In real life, I have a sister who’s very different from me. We were hiking together the other day, and I was in a hurry, as usual, to get to the top of the trail and down again. But my laid-back sister was content with a slower pace—a pace I sometimes find annoying. Because of this, she noticed many things I did not—including two snakes that I might have stepped on had she not pointed them out to me! In a story, my sister would be the character who looks down and finds the magic key or the missing item in the road. She would be the one who sees what’s important.

The process of transforming character faults from undesirable elements into something valuable is a kind of fictional alchemy. Pure story gold. If writers can stop thinking of limitations as liabilities and reframe how these traits are viewed, we’ll be rewarded with more innovative plot twists and satisfying endings. Personally, I like the idea that I don’t have to be someone different than I am to succeed. Don’t we all want to be loved and accepted for who we are? So, examine your characters’ weaknesses and put a different spin on these traits. If you need motivation, just look at Rossi’s video.

Stork’s message was fortuitously similar. “You must learn to trust your intuition if you want to write characters with heart and soul who live forever in the minds of readers.” Stork defined intuition as “a way of seeing a truth that is not dependent on words.” As the creator of one of my favorite fictional characters, Marcelo Sandoval from Marcelo in the Real World, the author clearly practices what he preaches. The truth of Marcelo, his “soul,” came to Stork in a flash of intuition. Later he tweaked and revised his protagonist, but because he trusted his gut instinct and embraced the “sudden illumination,” an extraordinary character was revealed to him.

Stork’s message was fortuitously similar. “You must learn to trust your intuition if you want to write characters with heart and soul who live forever in the minds of readers.” Stork defined intuition as “a way of seeing a truth that is not dependent on words.” As the creator of one of my favorite fictional characters, Marcelo Sandoval from Marcelo in the Real World, the author clearly practices what he preaches. The truth of Marcelo, his “soul,” came to Stork in a flash of intuition. Later he tweaked and revised his protagonist, but because he trusted his gut instinct and embraced the “sudden illumination,” an extraordinary character was revealed to him. While writers cannot force this kind of insight, Stork claimed that “we can create circumstances that are favorable for its arising.” He cited three writerly disciplines—mindfulness, a sense of play, and honesty—that make it “more likely for the lightning of intuition to strike.”

While writers cannot force this kind of insight, Stork claimed that “we can create circumstances that are favorable for its arising.” He cited three writerly disciplines—mindfulness, a sense of play, and honesty—that make it “more likely for the lightning of intuition to strike.”