While visiting my eldest son in Oregon this month, I spent a morning picking peas on his farm. After showing me how to choose the plumpest pods that were ready for harvesting, my son handed me a bucket to fill. As I worked my way down the row of trellised vines, peering out from under my sun hat into the dappled green depths, I picked what I thought was every last ripe pod.

While visiting my eldest son in Oregon this month, I spent a morning picking peas on his farm. After showing me how to choose the plumpest pods that were ready for harvesting, my son handed me a bucket to fill. As I worked my way down the row of trellised vines, peering out from under my sun hat into the dappled green depths, I picked what I thought was every last ripe pod.

It wasn’t until I went back for a second pass, that I saw the rogue pods that had escaped me. They seemed to have popped out like magic right in front of my eyes. I stared at them as they dangled jewel-like from the stalks, their plump exteriors bulging from the tender bumps inside. How had I missed them before?

One of the farm interns chuckled. “It takes awhile to get your pea vision,” he said, “and yours just kicked in.”

Pea vision, as I define it, is when something obscure becomes suddenly clear. It’s all about perspective. Writers need to find their form of pea vision too—especially when it comes to characters. Figuring out how a protagonist acts, thinks, feels and talks rarely happens in a single blinding flash of insight. It takes time to get to know a character. When I walked back down that row of peas, I saw things I hadn’t seen before. Why? Because I changed the way I looked at the vines.

Pea vision, as I define it, is when something obscure becomes suddenly clear. It’s all about perspective. Writers need to find their form of pea vision too—especially when it comes to characters. Figuring out how a protagonist acts, thinks, feels and talks rarely happens in a single blinding flash of insight. It takes time to get to know a character. When I walked back down that row of peas, I saw things I hadn’t seen before. Why? Because I changed the way I looked at the vines.

Searching from a new angle, picking pods from the other side of the trellis, and risking bug bites and sore muscles to kneel in the dirt enabled me to better see what was ripe for the taking.

In writing, a different vantage point can result in a similar bounty. Our stories play out in real life from a single perspective—our own. But in novels, we can narrate from multiple points of view. I’ve always loved books where different characters give their version of the same series of events. In books like Tim Wynne-Jones’ Blink and Caution, Cynthia Leitich-Smith’s Feral series, and Sharon Darrow’s The Painters of Lexieville, each narrator’s perspective fills in a piece of the story.

“Write what you know,” goes the old adage. But writers should do exactly the opposite too. Mine your life, sure, but stretch yourself as well to write what you don’t know, what you don’t understand, as a way of figuring it out. I love writing about people on the edge, for example. The people who trigger us—whose behavior makes our blood boil—can sometimes be our best teachers. The traits in them that most disturb us may tell us a lot about ourselves (and our fictional characters).

Which is why I like to give my writing students the following exercise: rewrite an existing scene in your story from the antagonist’s POV. The point is to write from the perspective of someone whose behavior is strange, disturbing or even incomprehensible. The goal is to find the commonalities, because I believe that people, no matter where we come from or how we grow up, have more things in common than we have differences. Afterwards I ask my students, “How did that change your story?”

Currently, I’m writing a book narrated from three points of view. One of the POV’s is my antagonist, a man very different from me. An obsessive-compulsive computer programmer with PTSD, he’s awkward, unattractive and antisocial. He has no friends and spends his days coding and his nights playing video games. He also commits a terrible crime. How do I get into his whackjob mindset? By looking for emotions we’ve shared, instead of the life experiences we haven’t. Like my antagonist, I too have felt lonely, jealous and powerless—and that is how I access him.

Writing from the antagonist’s perspective can make the invisible visible. It does so by enabling writers to understand things about the world of their story that they may not seen before. Both my antagonist and the teenage girl he’s obsessed with undergo pivotal transformations when they recognize in each other some of the emotional issues they struggle with themselves.

In addition, exploring the antagonist’s POV can help avoid stereotypes. In a recent VCFA lecture on diversity in fiction, author Cynthia Leitich-Smith talked about the challenges and rewards of writing fiction from the POV of multicultural characters who may be different from ourselves. (Differences, she pointed out, can manifest themselves in many ways such as ethnicity, race, gender, religion, socioeconomic levels, physical and mental health issues and abilities to name a few.) “Our characters shouldn’t be two dimensional excuses for social studies lessons,” Leitich-Smith said. “We are all accountable for the impact of our stories on young readers.” I came away from her lecture determined not to make assumptions. The danger of a single story is real.

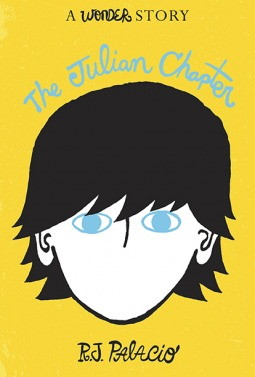

Third, writing about characters antithetical to ourselves cultivates empathy. Never judge a person’s insides by his outside, my husband frequently says. When I remember to do that, I can step more easily into the other person’s shoes, and our differences matter less. When Wonder author R.J. Palacio decided to write a new chapter from the bully’s perspective, many readers felt that Julian’s narrative was the best one of all. Bad guys may not be all bad, even when they do bad things. My antagonist is deeply flawed, dangerously hurt and he’s got a backstory full of baggage. But I didn’t understand all that until I began writing from his POV. I recommend two YA books, in particular, as stellar examples of antagonists who are protagonists: Tenderness by Robert Cormier and Inexcusable by Chris Lynch. Although the narrators are deeply disturbed teenage boys, I found myself still caring about them, despite their horrific acts.

Third, writing about characters antithetical to ourselves cultivates empathy. Never judge a person’s insides by his outside, my husband frequently says. When I remember to do that, I can step more easily into the other person’s shoes, and our differences matter less. When Wonder author R.J. Palacio decided to write a new chapter from the bully’s perspective, many readers felt that Julian’s narrative was the best one of all. Bad guys may not be all bad, even when they do bad things. My antagonist is deeply flawed, dangerously hurt and he’s got a backstory full of baggage. But I didn’t understand all that until I began writing from his POV. I recommend two YA books, in particular, as stellar examples of antagonists who are protagonists: Tenderness by Robert Cormier and Inexcusable by Chris Lynch. Although the narrators are deeply disturbed teenage boys, I found myself still caring about them, despite their horrific acts.

So go find your pea vision by getting curious about your antagonist’s world. Give him a mouthpiece, ask him questions and listen with your heart. How does it change your story?

How does it change you?